Publishing Papers

This document provides an overview of the scientific publishing process. It doesn’t actually discuss scientific writing at all; for that, check out some of the following resources:

- Writing Science is one of the top books on scientific writing available.

- Jeff Leek has a guide to writing your first paper; it’s focused on students writing theoretical papers with Jeff directly, so some parts are not broadly applicable.

How to Choose a Journal

Stephen B. Heard (Ecologist at UBC) has a pretty decent post on how he chooses journals when submitting a paper. The summary is something like this:

- Choose a journal when you have a rough idea what the paper will look like and what story you want to tell, but before writing very much of it.

- Choose a journal which would be interested in that story, and is the best-ranked journal you think you could publish it in.

Obviously, #2 is a lot easier said than done. Assessing how well your story “fits” a particular journal is really hard; you basically need to review their recent papers as well as their “Aims and Scope” page to see how well your story lines up with the papers the journal actually puts out.

Assessing the rank of a journal is also pretty tricky. Scimago ranks most journals on a few axes, including their impact factor and “SJR” score. Trying to interpret these metrics directly is pretty pointless; the main thing that matters is how they compare to other journals which “fit” your story.

Scimago also ranks journals within each field that they’re assigned to. You should generally be aiming to publish in journals that are in the top quartile (Q1) of their field.

Open Access

An important distinction when choosing a journal is whether or not it’s open access. In the “traditional” publishing model, you give your paper away for free to a journal, which then charges people (usually through their university’s library, though sometimes directly) to access your research. In the “open access” model, you pay a fee (usually between $1,500 and $3,000) and your paper is made freely available. Open access papers are generally cited more, and it’s typically argued that this is because they are easier to access, though the evidence is weak1.

You should not foot the bill for an open access publication. If you’re interested in publishing in an open access journal, ask Colin if there’s any money on your grant to support publication. If there isn’t, consider applying for grants to pay for the publication, or look into other ways to make research published in a subscription journal more openly available (for instance, submitting a preprint as detailed in Section 1.5).

There’s a lot of terminology around open access, most of it useless. Below, we use the terms “open access” to mean a journal that requires payment but will make your article publicly available, “traditional” or “subscription” to mean a journal that does not have an open access option, and “hybrid” to refer to a journal that allows either option. Note that some traditional journals still charge fees (often per page of your article); whether or not those journals are worth publishing in over an open access journal is up to you.

Potential Journals

This is a list of journals, organized by field, that lab members have had good experiences with or appreciate the outputs of. Please add any missing journals to the list!

Environmental Science

- Environmental Research Letters is an open-access journal for short (max 4,000 word) reports on “environmental change and management”. They have a long-running special issue on forest biomass modeling.

- AGU Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems is an open-access journal publishing “original research articles advancing the development and application of models at all scales in understanding the physical Earth system and its coupling to biological, geological and chemical systems”.

- Science of The Total Environment publishes novel, hypothesis-driven and high-impact research on the total environment, which interfaces the atmosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and anthroposphere.

Remote Sensing

- Remote Sensing of Environment is a hybrid journal publishing “results on the theory, science, applications, and technology of remote sensing studies”.

- ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing is a hybrid journal covering “the many disciplines that employ photogrammetry, remote sensing, spatial information systems, computer vision, and related fields”, with topics including “sensors, theory and algorithms, systems, experiments, developments and applications”.

- GIScience and Remote Sensing is an open-access journal publishing “articles associated with geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing of the environment (including digital image processing), geocomputation, spatial data mining, and geographic environmental modelling.” We’ve had luck getting weird, somewhat niche remote sensing papers published here.

- Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing publishes topics including sensor and algorithm development, image processing techniques and advances focused on a wide range of remote sensing applications including, but not restricted to; forestry and agriculture, ecology, hydrology and water resources, oceans and ice, geology, urban, atmosphere, and environmental science.

- International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation publishes original papers that apply earth observation data to the inventory and management of natural resources and the environment. The focus, which can be either conceptual or data driven, includes all major themes in geoinformation, like capturing, databasing, visualization and interpretation of data, but also issues of data quality and spatial uncertainty.

Ecology and Forestry

- Landscape Ecology is a hybrid journal publishing research on “the ecology, conservation, management, design/planning, and sustainability of landscapes as coupled human-environment systems.”

- Forest Ecology and Management is a hybrid journal publishing articles that link forest ecology to forest management.

- Methods in Ecology and Evolution is an open-access journal publishing papers on “the description and analysis of new methods and methodological approaches, not the results of applying existing or new methods”.

- Journal of Forestry publishes research on all facets of forestry.

- Ecography publishes exciting, novel, and important articles that significantly advance understanding of ecological or biodiversity patterns in space or time.

Other

- The Journal of Open Source Software is a low-prestige journal publishing extremely short (max 1,000 word) papers on open source software. If you write an R package or similar, and don’t want to conduct an extensive validation study to get it published somewhere like Methods in Ecology and Evolution, this is a good location. They’re also generally fantastic to work with, having an entirely open review system and extremely clear communication. All papers here are freely open access.

- Journal of Statistical Software is an extremely high-prestige journal publishing normal-length papers on, well, statistical software. This is a very good option for, example, stats-heavy R packages.

- International Journal of Geographical Information Science provides a forum for the exchange of original ideas, approaches, methods and experiences in the field of GIScience.

- Applied Geography is a journal devoted to the publication of research which utilizes geographic approaches (human, physical, nature-society and GIScience) to resolve human problems that have a spatial dimension.

- Geophysical Research Letters publishes high-impact, innovative, and timely communications-length articles on major advances spanning all of the major geoscience disciplines. Papers should have broad and immediate implications meriting rapid decisions and high visibility.

- The Software Sustainability Institute maintains a list of journals which publish software papers.

Journals to Avoid

Predatory publishers have become a real problem in recent years. These journals offer the appearance of peer-review and publication in a credible source, but in actuality are mostly just “pay to play” venues where, for a few thousand dollars, dishonest researchers can add another paper to their CV to pad their applications. These journals are typically open-access, in order to justify charging thousands of dollars for publication in a fake journal, but it’s important to stress that while most predatory publishers are open access, most open access publishers are not predatory.

It can be hard to tell if a journal is predatory without digging into their website and the quality of the work they’ve published. If you’re invited to submit a paper to a journal or special issue – particularly as a student or by someone you’ve never heard of – that’s a good indicator a publication is predatory. If a journal is affiliated with a large professional organization you’ve heard of (examples include AGU, ESA, BES, and SAF), they’re likely not predatory. Otherwise, you can always feel free to ask lab members if they’ve heard of a journal before, and what they think.

In general, we avoid publishing with the following venues, and don’t cite papers from them if possible:

- MDPI journals are not universally agreed upon to be predatory, but are pretty clearly not not predatory. Papers published in MDPI journals are not allowed to be considered in hiring in multiple EU countries.

- Frontiers journals are generally low-quality and should be avoided. Please note that while all Frontiers journals start with “Frontiers in”, the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment is not a predatory journal; the nearly identically named Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution is.

Submitting a Paper

Budget a day for submitting a paper. With any luck it will only take a few hours, but submitting a paper is one of those things that always takes longer than it really should.

The website of your target journal has a page, likely named “guidelines for authors” or similar, with a list of instructions for how your paper should be prepared. As an example, here’s the page for Forest Ecology and Management. You should review this page while writing the paper, to make sure your manuscript will be compliant with journal requirements. Before submitting the paper, go through this webpage again and make sure that your paper is compliant with every requirement; there’s nothing worse than having a paper rejected before it even gets to the editor because it’s missing some important elements.

Some common “gotchas” submitting a manuscript include:

One thing that catches a lot of people by surprise is that you’re expected to include a cover letter when you’re submitting a journal article. This is a relatively important document – as the editor in chief of Global Ecology and Biogeography puts it, the cover letter determines whether or not your paper will be one of the ~50% that get rejected by the editor without even going for review. Most journals will have a list of items to include in the cover letter as part of their guidelines for authors; make very sure your letter touches on every point. You can find an example of a cover letter used in our lab (for use as a template) at this link.

One of the most time-intensive steps of the process is preparing a list of suggested reviewers. Most journals will ask you to suggest 3-5 reviewers, who are familiar with at least some element of your paper and will be able to offer a useful review. Stephen B. Heard has some advice on who to choose on his blog. It’s often helpful to go through your citations and see whose name shows up on multiple of your cited sources; that person is probably a good suggestion.

One thing to note is that, depending on the journal, you’re going to need to supply each reviewer’s institution and email address, as well as a reason they’d be a good reviewer. This is extremely time-intensive to gather, and should your paper be rejected (Section 1.4), there is often no way to see the information you put into the system the first time around. It’s a really, really good idea to save a .txt file with this information in the same folder as the rest of your paper, just in case it comes in handy again.

Peer Review: What the Hell

Peer review is wild. You’ve just spent months of decently high-intensity work pulling together a small illustrated novella, spent a full day filling out fields in a system describing your novella for people whose names you will never know, and then all of a sudden all work on the project comes to a halt while you wait for months to hear back if those anonymous strangers liked it.

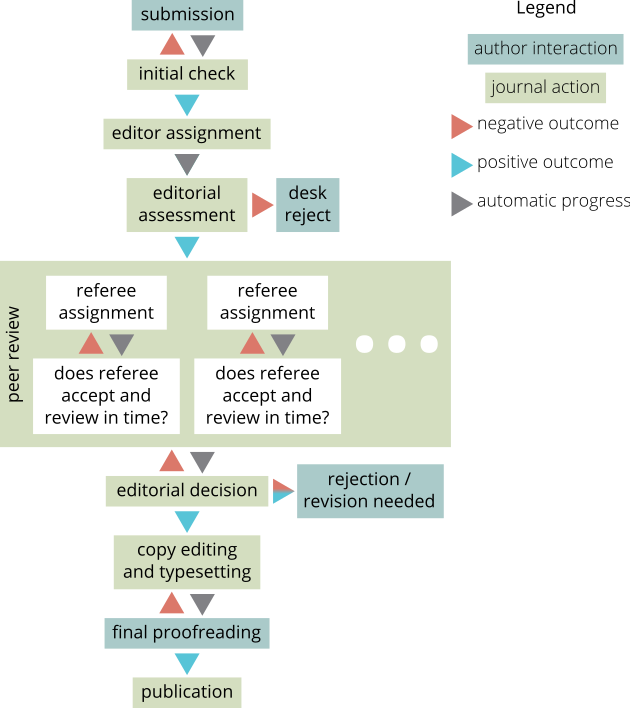

- After submitting your paper, it will go through all the steps in the above diagram, which are explained in more detail at this link. Whatever system you submitted your paper through probably gives you updates on whether the paper is “With Editor” or “Under Review” or any number of similarly cryptic phrases; these mostly don’t matter from the author’s perspective. Once you’ve submitted a paper, the only thing to do is wait.

- In our field, you should expect peer review – so the green box on the above diagram, not including anything outside the box – to take about 3 months. You probably shouldn’t email asking the journal for a status update before waiting 14 weeks.

- Despite those two items, and the fact you can’t do anything about your paper while it’s under review, everyone else also checks the system all the time for updates.

Your paper will probably not get accepted the first time you send it off. Getting “minor revisions” back is pretty much the best case scenario; if your paper gets accepted right away, without revisions, you probably should have sent it to a better journal.

Assuming you received a “revise and resubmit” (R&R decision), the first thing you should do is forward the reviewer’s feedback to all your co-authors, optionally with your first impressions of the feedback. It’s usually useful to schedule a meeting with your co-authors for a few days in the future, to allow time for rumination on the feedback, in order to plan next steps.

Once that’s accomplished, it’s time to actually revise your paper. In addition to producing a revised paper, you should usually also create a version of your paper with “highlights” everywhere that changes were made – some journals require this as an additional file when resubmitting a paper, but it’s often appreciated by reviewers even if not outright required.

In addition to actually making the changes, you’ll also need to write a “response to reviewers” report. In this document, you’ll respond directly to each line of each review, explaining exactly what you did to address the concern. There’s a good post with more advice on writing this report online at Dynamic Ecology.

It’s worth noting that peer review comments can often be mean, either intentionally or as a result of researchers not understanding how their tone in text reads to strangers. There’s not a great way around this, other than to know it happens to everyone; everyone in the lab is happy to hear you complain about the reviews you just got back. Stephen B. Heard has good advice here on dealing with idiotic reviews.

I Got Rejected: What the Hell

This is very, very, very normal. Most papers do not get accepted the first place they’re submitted. A decent chunk don’t get accepted round 2, either.

If you got a rejection email, here’s a few useful steps:

- Read the feedback you received from editors or reviewers, and forward it to your co-authors with your initial thoughts. It’s usually useful to schedule a meeting with at least some of the co-authors, a few days in the future, to discuss next steps.

- Take as much of the day off as possible. At the very least, work on something else. You are not going to be in a great mood, and giving yourself a little space to ruminate on the feedback will likely make you more receptive to any good points they did make.

- After meeting with your co-authors, revise the article using the feedback as if you were going to resubmit it to the same editor and reviewers. It’s very, very common for a paper to be sent to the same reviewer by multiple journals (especially if you’re using the same list of suggested reviewers), and nothing annoys reviewers more than learning they spent time to give an author feedback that was promptly ignored.

- Submit the paper to a new journal.

While most journals let you appeal a rejection, it’s rarely worth it. While reviewers can recommend a paper for rejection, the ultimate decision is made by the editor of the journal, and you need to have a very persuasive case for the editorial board (or whoever processes appeals) to believe your argument over the judgement of their own members. It’s usually a better decision to revise the paper and submit it to the next journal instead.

Preprints

As detailed above, the time between initial submission of a manuscript and final publication is typically measured in months, if not years. That’s a long span of time to have a project more or less finished without being able to claim credit for it, and it’s not uncommon for other groups to publish similar work in that timeframe and steal some of the thunder out from behind you.

One way around that is to post your work as a preprint. Preprints are versions of papers posted before peer-review, and let you break some of the secrecy that tends to build up around research projects without needing to wait for the peer review process to finish. In addition, preprints are freely accessible by anyone, and can help you make your work more accessible even if it’s not being published in an open access journal. While not perfect (for instance, preprints seem to rely more on academic “fame” networks for attention even more than regular publications), posting your work as a preprint can help reduce a lot of the downsides of the peer-review process.

Most journals are totally fine with you posting your paper as a preprint before it’s published. Some are not. If you’ve got your heart set on a specific journal, make sure they accept papers previously posted as preprints before you submit to a preprint server!

We generally post our preprints to arXiv when possible, because it is the largest preprint server and seems to result in the most attention. Papers from our lab generally qualify for inclusion under “stat.AP”2, and sometimes under “cs.LG”3. Work focusing on maps based off optical imagery (e.g. Landsat) has sometimes been reclassified by the system administrators as “cs.CV”4, which doesn’t make a ton of sense but likely reflects the absolute firehose of submissions arXiv administrators have to deal with.

Other good preprint servers include EarthArXiv for more Earth-science oriented papers, and EcoEvoRxiv for more ecology-focused studies.

Archiving Data

Many journals require data used in publications to be archived and made public post-publication. There’s a lot of digital ink spilled on the process of preparing data for archiving; some useful links on the subject include:

In general, these resources recommend the same basic set of considerations:

- Archive all data that underpins a publication, cannot be easily reproduced, or might be useful to others in the future, including all raw data.

- Don’t archive intermediate files and obsolete versions of files.

- Save your data in as simple a format as possible, preferring text files over binary formats which might become obsolete in the future.

- Include a clear description of how the data was collected, how it was processed, and what each variable or file represents.

Once your data has been prepared for archiving, you need to find an archive which will accept your data and host it for (theoretically) forever. There’s a million archives available; Scientific Data has a list of archives by field..

One of the most useful archives is Zenodo, which accepts a wide variety of research artifacts, is free for users, and is more user-friendly than the vast majority of archives. You can create an archive, upload your files, and get a DOI for your data set before actually publishing it publicly, making it a useful place to archive data before the peer review process. For this reason, we’ve started using Zenodo for a handful of lab projects.

One challenge with Zenodo is that it can be tricky to upload large files through the web interface. If you’re uploading more than 100MB of data to Zenodo, consider using the REST API instead to make the process easier.

Once you’ve created a new “project” (called “deposits” in Zenodo), you can use this script to upload files via the API:

# install.packages(c("httr", "glue"))

library(httr)

library(glue)

# Create a "personal access token" at:

# https://zenodo.org/account/settings/applications/

ACCESS_TOKEN <- "ChangeMe"

# The number at the end of your upload's URL:

# https://zenodo.org/deposit/<some_number>

DEPOSIT_NUMBER <- "ChangeMe"

# The actual name of the file, no path information

FILENAME <- "ChangeMe.Zip"

# Relative path to the file, from where your code is running

FILE_PATH <- glue::glue("./ChangeMe/{FILENAME}")

r <- GET(

glue("https://zenodo.org/api/deposit/depositions/{DEPOSIT_NUMBER}"),

query = list(access_token = ACCESS_TOKEN)

)

PUT(

modify_url(

paste0(content(r)$links$bucket, "/", FILENAME),

query = list(access_token = ACCESS_TOKEN)

),

body = upload_file(FILE_PATH)

)# pip install requests

import requests

# Create a "personal access token" at:

# https://zenodo.org/account/settings/applications/

ACCESS_TOKEN = 'ChangeMe'

# The number at the end of your upload's URL:

# https://zenodo.org/deposit/<some_number>

DEPOSIT_NUMBER = 'ChangeMe'

# The actual name of the file, no path information

FILENAME = 'ChangeMe.zip'

# Relative path to the file, from where your code is running

# Don't include the filename, it will be appended automatically (via "%s")

FILE_PATH = "./%s" % FILENAME

r = requests.get(f"https://zenodo.org/api/deposit/depositions/{DEPOSIT_NUMBER}",

params={'access_token': ACCESS_TOKEN})

with open(FILE_PATH, "rb") as fp:

r = requests.put(

"%s/%s" % (r.json()["links"]["bucket"], FILENAME),

data=fp,

params={'access_token': ACCESS_TOKEN},

)

r.json()Footnotes

The key challenge with this argument is papers are not chosen for open access at random, but rather represent papers that researchers are willing to spend a few thousand dollars on making publicly available. It stands to reason that people and organizations might be more willing to spend this extra money on papers they think are particularly important, and which would be cited more anyways.↩︎

“Statistics Applications: Biology, Education, Epidemiology, Engineering, Environmental Sciences, Medical, Physical Sciences, Quality Control, Social Sciences”↩︎

“Computer Science/Machine Learning: Papers on all aspects of machine learning research (supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement learning, bandit problems, and so on) including also robustness, explanation, fairness, and methodology. cs.LG is also an appropriate primary category for applications of machine learning methods.”↩︎

“Covers image processing, computer vision, pattern recognition, and scene understanding. Roughly includes material in ACM Subject Classes I.2.10, I.4, and I.5.”↩︎